|

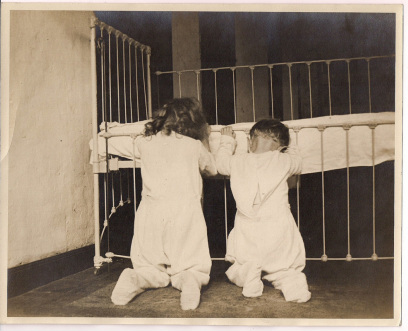

“God bless Mama-Daddy-Harry-Joanie-Tommy-Hazel-Jack-Bobby-Katie-Donnie-Rosie-and me, Emily,” I knelt on the wooden floor, in front of the not-big-enough double bed, with my sisters Hazel and Katie, in our too thin flannel nightgowns, passed down too many times. The cold climbed up our legs, through our kneecaps, like gladiola stems sucking up water in a vase. Mama held Rosie in her lap on the bed listening to our prayers. I kept one eye open. “Amen,” we chorused and climbed into bed. Me, Hazel and Katie slept together in the one bed. Rosie slept in Mama and Daddy’s room, still in her crib. We’d scootch over so she could move in with us next year, making it a foursome. Or, Hazel would leave. I knew she wanted to. The mattress creaked and groaned, protesting under our combined weight. Through no fault of our own, we rolled toward the sag in the middle. “It’s a school day tomorrow. No ruckus up here.” Mama turned out the light on her way downstairs with Rosie slung on her hip. We could hear “How Great Thou Art” in Mama’s off key soprano all the way down the steps, her ragged house slippers slapping her heels. We lay together in the dark, gripping each other’s clammy hands and waited. Almost every night Hazel murmured quietly, prayed, bargained, and cried herself softly to sleep. Sometimes he didn’t come. Most nights he was too drunk. We never knew if he would or wouldn’t. I stared at the ceiling, eyelids wide until they grew so heavy with sleep I couldn’t keep them open. I drifted off, Katie’s fingers intertwined through mine, a grip tight enough to make me lose feeling all the way to my shoulder. “Daddy, don’t. Please.” My eyes opened then whipped shut. My mouth filled with spit. Katie pressed her body against mine, hard. No air. We played dead so well, we almost were. Then we heard the slow, low metal sound of a zipper dragging down its ragged teeth. “No, no, no, no,” Hazel’s begging whisper. My skin felt prickly, burning hot. How long could I go without breathing? “Shhhh…now hush gal…give me your hand…” “Please. No.” “Shhh…shhh…” Katie pressed harder, the mattress squeaked. Our sweat-drenched gowns clung to our bodies, each other, and the threadbare sheet beneath us a dank pool. The coiled springs beneath us wheezed, keeping time with Daddy’s whimpering sounds. He sounded just like our dog Heidi when she had her puppies. Hazel cried. The wet smell stung my nostrils, mixed with the sour sickening stench that clung to Daddy. He rarely bathed or brushed his teeth. The raw meat and clotted blood he wore home from his butcher shop hung from his hair, stuck under his nails and smeared the front of his shirt where his apron didn’t cover - and the rotgut he swilled every night hung over him like a fog. Katie and I stayed straight and stiff, helpless against the onslaught of a father who reeked like a drunken, slaughtered animal. I gagged quietly in the dark. He left. Hazel rolled into a ball and sobbed without making a sound. We scooted toward her like we always did, but didn’t talk. Katie put her arms around Hazel’s back and I put my arms around Katie, a chain of girls, youngest to oldest. Like we did with Joanie. And like I will with Katie. She’s the next one up. Then it’ll be me. I’m not sure exactly what Daddy’s doing. I just know it’s bad and I know I can’t tell anyone, especially Mama. I know he takes his pants down. It makes me cry, and my stomach hurts all the time. I asked Joanie once, before she left home for good. She slapped me so hard my head hit the wall behind me, and my eyes bugged out. Then she knelt down, grabbed me tight, and pressed me to her chest. “I’m sorry, Emily, I’m sorry,” she said, her tears soaking my neck. “You don’t know anything. You’re just a kid.” I never brought it up again. No one did. I figure I’d find out soon enough. My guts churned. **** “Now you boys stay out of those woods,” Mama hollered after my brothers, Bob, Donnie and Jack, grabbing their lunch sacks, running out the kitchen door to school. The screen swung wide on its rusty hinges, and slammed. I never could figure why Mama fussed over the boys and those woods. They never took to ‘em. Not like me. Not far from our house, across from the Dietrich’s place, around from the burnt out Texaco gas station lay Doc Pritchett’s wooded land. Daddy called it 40 acres of waste ‘cause Doc would never clear, or sell it. Mama said he was too busy doctoring to bother with clearing or selling. But those woods made for a nice shortcut to and from. School was over a mile away. A quick dart through the corner section of Doc’s woods cut the walk in half. After the boys high-tailed it out I was the last one, stalling before school. “Dawdling,” Mama always said. “If I have to tell you to get going one more time…” Mama wiped baby Rosie’s Malt-O-Meal covered fat face off with the bottom of her apron and griped at me at the same time. “Girl, you’ll be late for your own funeral.” Why I would mind that, I couldn’t fathom, and said so. I snatched my brown bag off the chipped breakfast table quicker than she could swat me, elbowed out the screen door, and ran. Mama never said anything to me about the woods. She never did. **** I had good intentions, until I didn’t. I was running late. So, when I got to the place where I could’ve kept going the long way, I took the short way. I started through the woods to make up time. It got darker and cooler the deeper I went. At first, I walked fast. Then it was more like a lope. As my eyes adjusted to the dim light I gathered speed. Soon, I galloped along like a barn-soured horse at feed time. My feet hit the earth with sure strides. My leather soles crushed the dead leaves beneath them with a satisfying crunch, like smacking cornflakes in a paper bag with a rolling pin. I swapped my lunch sack from my left hand to my right and back again every few minutes. I felt sure I’d beat the clock. I galloped, grinning like the village idiot and about half way there when the toe of my two-toned shoe hit something soft, yet unyielding mid-stride. It stopped me cold, and dropped me like a sack of hammers. I landed on the dirt and twig covered ground with my, used-to-be-Katie’s, blue gingham dress up around my waist, with a thud and an oooof. The air slammed out of my lungs as my flat chest hit first, before my forehead, which made a sickening crack. I rolled onto my side and pulled my knees up. My head throbbed, sharp pain stabbed through it. I could hear myself moaning. I rocked from side to side on the sticks and leaves, trying to find air. After several minutes the cramps subsided. I could breathe again. I lay still. I wasn’t alone. My eyes, still shut tight, flew open. It didn’t occur to me to fake unconsciousness, which I’m good at. I sat up quick as Lazarus. Straight ahead of me was my lunch sack, sitting pretty as you please, where I’d flung it. I crawled back a few inches. There he laid, flat on his back, legs sprawled out, arms straight at his sides, neck bent at a funny angle. He looked broken - half covered in leaves, twigs, and dirt. From what I could see, he wore a dark suit and brown wing-tipped shoes like Pastor John’s. Or, like Mama would say, “a dandy.” I must’ve tripped over one of his legs. He didn’t look so good. I got close enough to poke him. His dark eyes peeked at me, barely open, the lashes matted and crusty. His mouth swollen, cracked, face green and sallow. He looked barely older than my brother Harry, who just turned twenty-one, and sickly, like he suffered from a bad case of the flu. His black hair slicked smooth, matted to his head. My eyes bulged like a bullfrog hit on the head with my brother’s flashlight, “You hurt, Mister?” I crept closer and saw the blood. His whole jacket soaked through with it, the ground beneath him covered in it. He smelled just like Daddy’s shop on slaughtering day, sickening, rank and sweet. I yanked my hand away and covered my mouth with it. Because I couldn’t help it, I studied his face. Even though I’d never seen a dead man before, I knew he was one. His eyes looked glazed, lifeless, like the lambs on hooks in the butcher shop. I started to cry. Usually, I don’t. Not unless there’s someone there to see me. I don’t know how long I sat next to a dead man, crying. He stank. I needed a plan. The only one I could come up with was to see if he had a wallet with something inside that might have his name on it. I used a stick to push his jacket lapel open. Nothing. I checked to see if the jacket had pockets, and found a folded up piece of paper and a stick of chewing gum. He probably carried his wallet in his pants pocket. How could I get him rolled over? If there was ever such a thing as dead weight – he was it. Luckily, I didn’t have to roll him far, more like a nudge. I scrunched up his wooly jacket, reached into his trouser pocket, and picked out his wallet - shaking the whole time. I didn’t look in it. I couldn’t waste more time. I snatched my lunch bag off the ground, threw in the folded up piece of paper, and the wallet. Thinking twice, I grabbed the gum and threw it in, too. No sense wasting a good piece of gum. It still had the wrapper on it. I ran for my life. One of us had to. It wasn’t going to be him. **** When I made it to class, I told Miss Parker I fell, which is why I got there late, and why I had a blue lump on my forehead. How I would let a grown-up know about the poor man, dead on Doc Pritchett’s land, I didn’t know just yet. If my mama knew I’d been in the woods I’d get the switch for sure. I’d have to think of a way to let someone know without tattling on myself. I’d have to worry about that later, after my head stopped hurting so much. He wasn’t going anywhere. **** “Emily, stop daydreaming, we’ve got customers,” my brother Harry said. It was my Saturday to help in the butcher shop. I ran scared. I’d gotten away with lying so far, but I still couldn’t think of a way to let anyone know about the dead man. Not without heapin’ a whole lotta trouble on myself. Luckily, with so many kids, Mama couldn’t keep us straight. I made her think she already knew I fell and hit my head against the table. All us kids tricked her like that. She just nodded and said, “It’s a long way from your heart” and went on about her business. What if I didn’t tell? The dead man would be no worse for the wear. I, on the other hand, wouldn’t be as lucky if my mama found out where I’d been. I kept my eyes on the ceiling, expecting a wallop from the heavens any second. The dead man’s wallet fit easily, tied around my waist, under my baggy dress. In a house with seven of ten kids still in it (there would've been eight, but Tommy had joined the Navy in ‘39), there’s no place safe to hide anything. But it kept coming loose, and I worried someone could see the bulge, even under my apron. “Harry, you get lunch. I’ll go after. Bring some back for your sister,” Daddy said. “Emily, get some more ground beef outta the walk in and hurry it up, you’ve been worthless all day. Head in the clouds.” I ran back to the big freezer and opened the heavy door with both hands. The icy blast of air hit my face like a slap. My jerking on the door loosened the wallet, and it slid down toward the ground. I crouched and caught it near my knees. I finally opened it. Earlier, I shoved the piece of gum, and folded up piece of paper in it, but couldn’t get away from prying eyes long enough to look at anything. His driver’s license read Wayne Hendrickson. He’d lived on West 58th Street, only 10 blocks from me. I unfolded the piece of paper, and read the type written note -“Everyone knows what you’ve been doing. You’re going to pay and rot in hell.” There were two, one-dollar bills in the fold. More money than I’d ever had in my life. At a penny apiece…I couldn’t even figure out how much candy I could buy. I knew it’d be a lot. I tucked the note back into the wallet and tied it onto my waist again, grabbing as many packages of ground beef as I could carry and went out front. Customer after customer came into the shop that day. Daddy’s butcher shop sat next to the town’s grocery. The grocery sold a lot of things. Like candy. All I could think about that afternoon was the two one-dollar bills. My mouth watered dreaming about the Tootsie pops and the Good News bars I’d soon eat. What could it hurt if I took just one dollar and bought some? The dead man couldn’t use the money. I looked up at the ceiling…so far, so good. I went to the restroom, loosened the string, grabbed a dollar bill out of the wallet, and waited for an opportunity. Harry’d gone home. Just Daddy and I stayed behind the counter. I should have thought of it earlier, before Harry left. Mrs. Wolanski took her pork chops off the glass counter, turned and walked away. I made my move. “Daddy, I’m going to get a soda at the grocery,” I said, cool as mama’s cucumber and purple onion salad. Hoping against hope he wouldn’t ask what I planned to pay for it with. Without looking at me, Daddy said, “We gotta clean up.” He shook his gray head. “Go on. Just go on and go home. You haven’t done me any good all day.” Victory. I’d forgotten Daddy had no interest in me. Yet. **** I heard my brothers say that Daddy came home drunk, barely standing, and late, that night. He stayed home two days in a row, walking around the house white as a ghost, and acting like one too. Never saying a word. Mama pestered him to go to the doctor. He sits on the edge of whatever chair he’s in and his eyes dart back and forth like a lizard looking for flies. Last night Donnie walked up behind him and said, “Daddy,” and he liked to put my brother through the wall. He stopped coming to our bedroom. I still felt scared. **** “Let the church say, Amen.” Every Sunday, Mama shuffled all of us off to church. Daddy never liked it, but he always went, and this Sunday was no different. He looked poorly too. It’d been over a week since he’d come to our room in the middle of the night. But I had other things to worry about. I’d been pondering my dilemma while we all loitered in the vestibule while Mama chatted with Mrs. Olsen and her spinster daughter, Olive. Trancelike, Daddy lurched into the church toward the pews. My brothers tumbled behind him. My sister Joanie stood with her husband Andy, and us. Joanie didn’t come to our house anymore. She got married quick, and now we only saw her here, on Sundays. Mama cried over it about once a month. I’d been thinking hard about how to have my candy and eat it too when I heard Joanie whisper, “…she’s messing with that furniture salesman, Hendrickson. Walt, or something or other.” I’ll tell you, I thought my tongue would fall out. Before I could drop dead, Olive whispered back, “And Nora’s a married woman…” “I know who-” I started to blurt out what I knew, but got a good cuff for my trouble. “Emily. Hush,” Joanie hissed. “You don’t know a thing about it. You’re just a kid." I kept my mouth shut after that. Most of the sermon passed in a blur, despite Pastor’s fire and brimstone threats. Bored, I gawked around, and who sat behind Daddy but Nora and her husband – Nora - who messed with Walt, or something or other, Hendrickson. Now, I didn’t know what “messing” entailed, but I caught a clue that it wasn’t good…apparently being married had something to do with it. From what I could recall, poor dead Wayne Hendrickson didn’t look old enough to mess with anyone. Nevertheless, he had enemies. According to the note, they knew what he’d done (and it must’ve been bad) meant for him to pay and burn in hell. I couldn’t figure out what, if anything, any of it had to do with Nora and her “messin." On cue, Pastor John, boomed, “Your sins will find you out!” and pointed right at Nora, directly behind Daddy. I jumped, and almost gasped. Before I could, Daddy sprang out of the pew, and bolted toward the door. **** The trail of blood led from Mama and Daddy’s bedroom to the bathroom, some on the white walls, drips, drops, splats, now congealed and almost black. “He’s sleeping now.” Doc Pritchard closed the bedroom door. “Close call, but he’ll be fine. He stitched up real nice.” Mama sobbed into her tissue, Rosie slung on one hip. Katie stood next to me, silent, lips pressed together so hard they’d all but disappeared. Hazel sat in Mama’s chair in the living room, staring out the window. “Why would he slit his wrists?” Mama almost wailed. “I don’t know if you don’t,” Doc Pritchard said. “He ran out of church like it was on fire. Something’s been weighing heavy on him,” Mama said. “I don’t know what.” Katie finally spoke, but she sounded funny. Like her back teeth were glued together. “When we got home, we saw the blood. I followed it to the bathroom…” She straightened her shoulders. “…there he was…on the floor.” “The razors still on the rug, by the bed.” Mama hiccoughed out the words. I tiptoed to my bedroom, worried that the look on my face would give me away. Somehow I felt at fault. God was punishing me for my deception. I needed to come clean. I could tell the Doc that a dead man lay rotting on his land. I could confess that I had his wallet, his money (well, most of it anyway) and his gum (no, I chewed that. It was stuck under our dresser for more chewing later). I could admit I’d lost his note. I could’ve…but…I didn’t. I wanted more candy. I still had a dollar and a half left. But, that posed another problem. The day I lost the note, the day I went to the grocery instead of helping Daddy clean up, Old Lady Taylor, the cashier said, “My, a whole dollar? How did a little girl like you get so much money?” I thought she’d call Mama, but just as my lip started trembling, Larry the bag boy with crooked eyes, dropped a bottle of Coke. It exploded on the concrete floor like a 4th of July firecracker. Old Lady Taylor hustled off to yell at him and I busted outta there like a rat with its tail in a trap. I ran my hand under the mattress, felt the wallet in its hiding place and decided to wait and see. **** The weeks passed. Daddy’s wrists healed and he went back to the butcher shop. No one mentioned “the incident,” at least not in my hearing, or out of my hearing when I snooped. Daddy still hadn’t come to our room and he still looked real sick. Mama got skinny from fretting, and I’d never seen Hazel happier. I’d waited so long to tell about dead Wayne Hendrickson and the lost note that I almost forgot it happened. My mouth stayed shut, my secret kept. His wallet lingered under our bed, the money still in it. I didn’t dare risk another candy buy. Time marched on. When the cops came to the store, it was my Saturday at the butcher shop. I saw the two of them, their dark blue uniforms sharp and crisp. They wore their hats at a jaunty angle on their heads and their badges shone, fastened to their chests. They had their heads down, talking low to my brother Harry, at the front of the shop. The jig was up - they’d finally come for me. What could I do but face the music? A life of crime wasn’t for me, not anymore. From behind the meat counter, I wiped my sweaty hands on my apron, then untied it and took it off. I could feel the tears gathering behind my eyelids. I took a step toward my fate when the gun went off. I didn’t know it was a gun then. I’d never heard a gunshot before. I heard a deafening, ear-ringing crack, felt the back of my neck and arms get wet. My shoulders vibrated. I saw my brother Harry’s face crumple; the cops jumped and ran toward me. The bright red splatters on the glass counter in front of me made me turn around, wondering where they’d come from. The wall behind me looked like Rosie’s highchair tray when she ate spaghetti - red everywhere, and something else. Something gray and gummy ran down the white tiled wall, some stuck there like the chewing gum under my dresser. Daddy lay crumpled on the ground, one eye open. The other eye was gone, along with most of his head. I think I saw it, or part of it, rolled up against the baseboard. The same gray slime running down the wall with the blood dribbled out of the stump that was Daddy’s skull. I don’t remember the rest of that day. **** It’s just us kids and Mama now. Harry runs the butcher shop. Me, Katie, Hazel and the rest of the boys help out. Rosie doesn’t care what anyone does. Joanie and Andy come over for dinner after church every Sunday. Tommy's coming home on leave next week. Hazel sings us to sleep at night. I didn’t know what happened for the longest time, other than Daddy shot his own head off. I didn't even know he had a gun. I’m pretty nosy though, a “busybody” Mama says, and that’s how I heard. Somebody found poor, dead Walt Hendrickson. I don’t know who or how. The cops came to the store that day to ask where Nora lived. Folks not familiar often stopped at the grocery or the butcher shop to ask directions, especially since the gas station burned down. Nora’s husband had killed poor Wayne. I never did know Nora’s husband’s name. I guess Wayne’s “messing” with Nora really was bad - bad enough to make her husband kill him and leave his body in the woods. I held my breath wondering if they’d say anything about Wayne’s missing wallet. I still had it under my bed, but I finally threw that old chewing gum away. It didn’t taste like anything anymore, so I had to. I don’t know why Daddy blew his brains out. I heard they found a note in his pocket. Maybe that explained it, but I don’t know. I’m just a kid.

15 Comments

The head-on collision didn’t kill me.

My cell phone wasn't so lucky. “…Sandy…Carol’s…she’s in…” I deleted the message. I’d had no messages until about 20 of them popped up all at once on my cracked cell. Hiding, no doubt, till safer terrain prevailed. Sandy. Not familiar. Carol…hmmm…oh right. Carol. From the remaining, wounded messages, I cobbled the story together. Carol was in hospice. Sandy left several voicemails with the details. The cancer that lurked in Carol’s sinuses marched on undeterred. “Sandy called. Carol is in hospice,” I said to my husband. “Carol who?” His face squinched up. “Sandy who?” “Carol, My dad’s wife…remember?” I mulled a couple seconds. “I think Sandy is one of her daughters.” “Oh,” he nodded. “Never heard of Sandy, I kind of remember Carol, I barely remember your dad.” You and me both. “I should go.” “Where?” “Vegas. I hate that he’s alone when his wife is dying.” “Why?” he said. “He’s never given a shit abou-” “I know.” *********************** He shuffled closer, arms swinging, legs stiff but bent like a marionette without enough strings, looking 20 years older than when I’d last seen him. “Dad?” Lurching through the airport crowd, he grabbed my carry-on in silence and kept going. “Dad?” “Hmmm?” He glanced back. “We’re going to the car.” His watery eyes widened, brow raised, a thin line of panic snaked through his voice. “Yeah, we are…I guess…” I followed. That’s it? I hadn't seen him in years and that’s all he had to say? No, hello, or so good to see you? When I let him know I planned to come he'd sounded distracted, which I kind of expected, considering. Not true. I expected some gratitude. At least a lilt of surprise in his voice, some sign he felt pleased that I would make the effort. A hair of shame tickled up my neck. No expectations – I’d come for him, not for me. Something wasn't right. We'd walked around the parking garage several minutes before it occurred to me he didn’t know where he'd parked his car. “Are we lost?” I asked. He stopped short, his shoulders drooped with the weight of an unknown burden. “Where are we?” My carry-on slid from his grip to the concrete. *************************** “He spun in circles all around the parking garage,” I whispered into the phone to my husband. “He ran up and over the medians into oncoming traffic, like three times. I thought he was gonna kill us both.” “What’s wrong with him?” “If I had to take a stab, I’d say Alzheimer’s, dementia or something.” “He recognizes you though, right?” “Yeah, but he doesn't know where he is or where he’s going.” I leaned against the sink. “He just acts weird.” “Where are you now?” “We made it to his house – a miracle. I’m in the bathroom, hiding.” I inched the door open a crack to peek out. “He’s got a chair turned over in the living room. Fixing it with his ice pick.” “Wow. That is weird.” “You're telling me.” I leaned in to make sure my dad couldn’t hear me. “There’s a hole in the wall where he put his fist through it.” “I should’ve come with you. No telling what he might-” “He can barely stand. I don’t think he’s a threat. Not anymore.” “How’s Carol?” “Same, I think. I haven’t seen her yet.” I checked my watch. Time for a drink. Please God. “Tomorrow morning we're going over.” “Well, maybe you can head back early. Not anything you can do any-” “I gotta go. He’s unplugging the TV.” ******************************* “What are you talking about?” “Dad, give me the keys.” I'd just loaded the dishwasher with our breakfast dishes. “No. I can drive fine. What’s the matter with you?” “The sooner you give me the keys the sooner we can see Carol.” “You don’t know where you’re going.” Shit. That made two of us. His eyes filled, he shook his head. “She just lies there. Doesn’t even open her eyes. What am I gonna do without her?” He wiped his face with both hands and breathed out, heavy. “How long have you been here?” I wanted to reach out for him, but didn’t. “Let’s go, Dad. You can tell me how to get there. You’re tired, too tired to drive.” He surrendered his keys. “How much do you think I can get for her car?” ******************************* “Something is definitely wrong with him,” Sandy said. After a quick introduction, we huddled in the corner of her mother’s hospice room. “I told my mom we should call you, let you know. But, she was afraid he’d find out, afraid of what he might-” “Yeah, I know the drill. I don’t blame her.” My eyelids felt heavy, the air trapped in my chest. “I don’t know what I could’ve done about it anyway.” Or what I can, or want, to do about it now. “He’s in pretty bad shape,” Sandy nodded her head in my dad’s direction. He sat perched, like a parakeet before flight, at the edge of the small sofa in the room, his eyes murky, full, mouth half open, nearly catatonic. “Let’s go,” He jumped to both feet, startling us. “I want to get an ad in the Penny Saver to sell Carol’s car.” ****************************** “Pull over. You don’t know where you’re going.” I jumped, surprised by his screech in my ear. “What are you talking about? I’m going the same way we came.” I drove on. He grabbed the steering wheel, hurtling us into oncoming traffic. I shoved him sideways and cranked the wheel back. We skidded back into our lane, horns screaming, cars swerving. He rammed both fists into the dashboard, his face purple, contorted. “GIVE ME THE FUCKING KEYS,” he yelled, spittle flying out of his mouth. I veered to the side of the road, my heart racing like a rabbit’s. I stopped. “Get out,” I said. “What?” “I said, get out.” I couldn’t look in his direction. “You almost killed us. Get out.” “YOU almost killed us. You’re stupid. You’re head’s up your ass. If you’d just give me the goddamn keys… Don’t cry. Don’t cry. My hands shook, but I said nothing, kept staring straight ahead. From my periphery I saw his head fall forward. “I’m sorry…that’s no way for a father to talk to his daughter.” He wept, wiping at his still red face. “Say you forgive me.” He pled, a desperate tremor in his voice. “Please, say it.” I shrugged, not trusting myself, or him. “SAY IT,” he screamed. I pulled back out onto the road. ********************************** “Are you hungry?” It’d been a bad day. I never gave eating a thought until I noticed the sun lowered over the mountains. My dad hovered over his checkbook, muttering, painting Whiteout on his ledger, painstaking, careful strokes. “This isn’t right…” I tiptoed behind him, peering over his shoulder. BAM! For the umpteenth time that day, I nearly bolted out of my skin. He slammed his tight fist on the tabletop. “This isn’t right, they’re taking my money.” He turned his head to glare at me. “I told that bitch at the bank I’d turn her in if she didn’t stop stealing from me.” I slid his check register closer. He’d scribbled numbers everywhere. It looked like John Nash’s chalkboard. Every white space covered in numbers with the occasional thick Whiteout skid mark written over in red ink. “I’ll take care of it tomorrow, Dad.” My molars hurt from gnashing. “You need to eat.” His face lit like a flashlight shone on it. “We could go to Marie Callender's. I know where it is.” He grinned like a 3 year old. "No, I'm gonna cook you something." "You are?" He clapped like a three year-old. “Ummm…well…yes.” His mood swings destabilized me. “I got some stuff at the grocery store to make chicken soup.” “Soup?” His face stretched open, delighted. “I love chicken soup…I didn’t know you could make it.” He toddled to the recliner, plopped down with a sigh, folded his hands in his lap. Waiting for his soup. ************************************ “Where are you now?” “In the bathtub.” “Where is he?” “Taking his computer apart with a turkey baster and a cheese grater.” “Any more incidents?” “No, dinner went peacefully, thank god.” “I could fly out and be there in the morning.” Husbands worry when their wives try to corral psychotics. “It’s fine. I don’t know what good I can do here so I’m gonna have to head home soon. He can’t live alone, and for Christ’s sake he shouldn’t drive,” I gulped my wine. “No way he’s giving up that car though. And I don’t think he’d agree to move somewhere else.” I chewed off a big doughy bite of my glazed donut. “Where would somewhere else be?” “I feel like it should be with us. He’s my dad.” I could hear breathing on the end of the line. “Are you there?” “Yeah…look…this is up to you. I know he’s your dad…but he’s never done one thing for-” I started crying, surprising myself. I held my half eaten donut out of the bubbly water. “I don’t know what I should do, I only know it doesn’t feel right to leave him to fend for himself.” “I know…I just-” “I don’t even know if we could handle him. He’s mean, maybe meaner. Unpredictable. I’d think some kind of an assisted living would be better equipped.” I swallowed a lumpy, sugary ball of heaven and chased it with a swig of Chardonnay, let my tears dry without wiping them. “I don’t know…” “Does he have the money for that?” “No idea, but I doubt it. He agonizes over his checking account and wants to sell Carol’s car. I talked to the bank teller, he’s got about $3000 to his name. But, I don’t know what he owes, where. He’s got a brand new car, already scratched and banged up, I’ll bet it’s not paid for.” I sat up far enough in the bubbles to pour another glass of wine. “The teller made it pretty plain he wasn’t welcome back at their bank. They try to help him figure out his bills, write checks, and he accuses them of ripping him off.” “Man, what a mess. You don’t think they’re ripping him off do you? I mean he’s a prime target for-” “No. I think they feel sorry for him, he’s alone, obviously ill…” I bit off another cloud of deliciousness. “No good deed…” I chewed with vigor. “Of all the men to end up without a wife.” “Carol’s still hanging on, right?” “Yeah, just a matter of days, or hours. No one knows. Poor woman.” I could hear his wheels turning. Considering, discarding. “Carol was…is…his sixth wife?” “Eighth.” “Jesus.” I imagined his eyes rolling. “You’re eating in the bathtub?” “Donuts…and wine.” Nirvana. “I’m not getting out till they’re all gone…” “FUCKING COMPUTER.” “…Or until my dad goes berserk. I gotta go.” *************************************** “I think you broke it.” I said. The keyboard looked bent, hanging off the table, teetering. The monitor cracked. “I need to get that money.” He paced back and forth, a stilted hobble, his feet going forward, not leaving the ground. “What money?” I pushed my wet hair out of my eyes, still gripped my wineglass. “Carol has money in her account. I need to get it.” “She has her own account?” Smart woman, Carol. “Well, yeah…but she wants me to have it.” He banged the keyboard for good measure, sending it sailing to the tile floor. “What’s all that?” I pointed to a heap. “Stuff from Carol’s closet.” I peered over the top of several haphazardly packed boxes. “You can take whatever you want.” “Dad…she isn’t even…and she has daughters…they should-” My eyes went right to it. “Why is this packed?” I held up a framed photo of my dad and me, circa forever ago. I realized there were several framed photos around the house, here and there. None of me, or my family. I dug through the box - two more photos of my kids, lay face down at the bottom. His face stayed blank, “Why not? I told you, you could have whatever you want. Take it.” I close my eyes to keep the tears in and put the photo back in the box. “No, that’s okay.” “Is there any more of that soup left?” He bobbed to the next thing, like an ostrich. “I didn’t know you could make such good soup.” “Yes.” I gathered myself. “I made a lot of it, so you could have leftovers, later.” When I’ve escaped. "You know..." he gave me a smug smile. "It could still happen for me." I turned the heat up under the soup pot. "What could?" "You know..." He kept grinning. "Another woman." "Wha-" "I'm still pretty young," he said. Speechless, I stirred the chicken around in the broth. “HEY! I have an idea. You wrecked your car, right?” He switched gears, all of a sudden he could remember. “Yes.” “Well, I’ll give you my car. I’ll keep Carol’s and you can have mine.” “No…I don’t want your car…thanks-” “You can just have it.” “No…” “….and I’ll make the payments for you.” “Payments? I don’t-” He giggled, giddy, excited about his good idea. “Yeah, I’ll make the payments for you…for the first six months.” “Ummm…no…thanks, but no.” “Come on, it’s a good deal.” He stopped pacing. “I’ll make the payments for the first three months.” “Dad. Stop. I don’t…” “It’s a great car. Brand new, Chrysler. You drove it.” He waved his hands, animated, face flushed. “All you have to do is take over the payments.” **************************************** “Flight get in okay?” “Yeah, just walking out to my car.” I adjusted my sunglasses. “I’ll be home in 20 minutes.” “Carol?” “That woman is tough. She’s still hanging on.” I shook my head. “Ten days now, no food or water. She looks peaceful though, sleeping.” “What’s gonna happen with your dad?” I sighed, loud. “I don’t know. His doctor says his dementia seems pretty advanced. He shouldn’t live alone..blah, blah…nothing I didn’t already know. Sandy graciously offered to keep an eye on him while we figure out what to do. Social Services said no one could force him to do anything he doesn’t want to do. Unless he kills someone, then the police will come but until then…” “Knowing him, killing someone is a possibility. If I were you, I'd let it go. He doesn't deserve your help.” “I know, I know…I just can’t let him wander the streets can I?” Anxiety’s prickly fingers ran up my neck. “We can talk about it this afternoon, when you get home from work.” I saw seven voicemails on my phone, left during my flight home. All from my dad. He’d written my phone number down in giant numbers and had me tape it to his phone. “ARE YOU THERE? I KNOW YOU CAN HEAR ME.” “SOME FAT BITCH FROM SOCIAL SOMETHING OR OTHER CAME HERE. YOU'RE RUINING MY LIFE.” “PICK UP THE PHONE. I HATE YOU. YOU CAN’T TAKE AWAY MY CAR.” “I’m sorry. Say you forgive me. I shouldn’t talk to you that way. Say you forgive me. PICK UP THE GODDAMN PHONE.” I deleted them all. I turned into the driveway at the same time my phone rang. Him. “Dad?” I braced myself for the barrage of abuse. “What are you doing?” He sounded young, vacant. “Just getting home.” “Home? Oh…did you go somewhere?” I rubbed the creases in my forehead with my free hand. “Oh…nowhere special. What are you doing?” “I’m heating up some soup. I think its left over from Marie Calendars. I went there…before….Do you want to know what kind it is?” I felt my heart break. She doesn’t look like the Devil’s spawn lying there.

Her eyelashes are so long they tangle on the ends. At rest, they flutter on her cheeks like wings fanned out, angelic. Ironic. Her blonde hair mats, sweaty from sleep. Her bangs lie crooked, scraggly from a self-inflicted haircut. A pink ring circles her mouth, a permanent kool-aid moustache, an oddity I can’t figure. More proof she’s otherworldly. I’ve given up trying to get it off. I lean down to kiss her. For the first time today I don’t feel like strangling her. I can feel tears well. I get up to leave. I haven’t said one kind word to her. We have days like this more often than not now, she and I. I tell myself I’ll treat her better the next day, that maybe it’ll make a difference. I back out of her room, holding my breath…terrified I might wake her. She just started sleeping through the night a month ago, even though she’s three-years old. When she learned to walk she’d climb out of her crib and run, anywhere, everywhere. By the time she turned two she’d unlock the front door, go outside in the middle of the night. I barricade the door now to keep her in. I don’t know what she might do if she got loose. I go to bed, lulling myself to sleep with my usual fantasy – getting sent to prison. Like a lot of mothers, I didn’t get how tough it’d be…parenting…especially this gig. She’s shot out of bed every morning at dawn as if from a cannon, her room an explosion of discarded clothes and toys. She changes her clothes four or five times a day, each outfit more bizarre than the last. How she loves each one, complete with tiara, knit beanie with earflaps and pom-pom, or some other kind of weird make shift hat-like contraption. No color or pattern combination is off limits – clash is an aspiration. After a troubled sleep, I hoist myself up, dreading the day. Some nights sleep eludes me. Others, I’m out like the dead. Best not to dwell on that too much. This morning she blows into the kitchen in red, white, and blue plaid leggings with a pink and white polka dot top, inside out and backwards. Her black patent leather Mary Jane’s are on the wrong feet. Her head is sans chapeaux but she has made a tremendous effort with three ponytails, not one where it should be. Even though he is used to these daily Dali-esque fashion shows her brother still gives a shout out to Einstein’s insanity definition, and says for at least the fourth time this week, “That doesn’t match.” He gets up to feed his parakeet before it’s time to catch the school bus. He saved up birthday and Christmas money to buy what I think is an odd pet for a kid. We already have a dog, which she has pretty much commandeered. I guess he wanted something of his own. He bought the bird, the cage, the feeder…the whole shebang. It took him weeks to choose the right colored parakeet, finally settling on the greenish variety. What can a kid do with a parakeet? He can’t pet or walk it, but he loves the thing and spends hours in admiration. He never has to be reminded to take care of it. He never has to be reminded to do anything. Patient and magnanimous, he says, “Do you want to help me feed Gideon?” “No,” she growls, her voice rough, like her vocal chords were dragged over a cheese grater. She climbs up on the kitchen chair, her patent leather clad feet pointing in the wrong direction, kicks the dog under the table. She accepts no invitations and offers no explanations. I hug him on his way out the door, this sweetest of boys, and wonder why he keeps trying. “The bus!” she barks as it goes by the kitchen window. She’s been talking for almost two years and I keep thinking she’s putting us on – with that voice. It’s frightening coming from the mouth of such a little girl. All the more disconcerting because she looks so precious. Shirley Temple opens her mouth and Herman Munster roars. It’s a cliché, really. I keep hoping she’ll use a different voice – a sweet, melodious one that matches her face. A mother at the playground suggested I take her to the doctor. I’m thinking a priest. Breakfast is the usual battle of the wills requiring negotiation skills worthy of a Secretary of State. She eats a few bites of toast, grudgingly, darts out of the kitchen, multiple ponytails wagging. The morning passes with two tantrums, one broken picture frame, and a lost, then found, super hero action figure stolen from her brother. I’m considering peanut butter for lunch when I hear bell sounds ringing faint, from a distance. She bolts out of her room, decapitated Barbie in one hand, plastic sword in the other. I wonder briefly if they’ve come for her. It’s the ice cream truck. Great. Ice cream before lunch. Resigned, I head for my purse to fish out a dollar. She’s already gone. I go to the window where I can watch her. She’s on her second outfit, striped shorts, flowered turtleneck with black lace tights and mismatched tennis shoes; one Dora the Explorer and one Converse. Two of the three ponytails have long since cried uncle, the last one barely hanging on. The little boy who lives in the building next door sidles up beside her, pushes in front of her. My heart pounds and burns in my chest. I feel myself go stiff, girded for the worst that still hasn’t come. My feet feel crazy glued to the kitchen tile. I can feel her stillness. Her presence on the sidewalk swells, takes up all the space. The boy lurches away from the truck, like a misbehaving dog yanked by a leash. She doesn’t stir. I see her lips moving, her rosy moustache jerking, changing shape. Something passes between her and the boy. He runs. She pirouettes on mismatched toes at the truck window, rising to her full height to peek over the ledge. She gets her ice cream. I remember I’d given her no money. I’m rooted, unmoving - just like she wants me. I see the boy who’d run scared sitting on the sidewalk a few feet away, crying. My feet leave the ground, suddenly unrestricted. I swoop outside and scoop her up with one arm. She dangles there, under my armpit, looking like a bag lady dwarf, waving to the sniffling little boy. She squirms to the ground, her permanent pink moustache twists her face into a smug grin, like the Joker bidding a temporary adieu to Batman, confident they’ll meet again over a burning Gotham. In the house, I open the fridge in search of jelly. The dog is on the bottom shelf. No idea how long he’s been there. Not long enough to suffocate, but long enough to have eaten or ruined most of the food. I try to pull him out. He digs his paws in, doesn’t want to come. I have to drag him. She strides in, gleeful. Poor dog takes one look and yelps, scrambles so fast in place, on the slippery linoleum. He clack-clack-clacks for about ten seconds before he gathers traction and high-tails it out. He’s afraid of her, of what might be next. Take a number, pal. “Did you put the dog in the refrigerator?” Some idiot sounding a lot like me asks her. “Yes.” she barks, nodding and clapping her hands. She is elated that I’ve discovered a deed long since forgotten. Smiling so proud like she’s donated an organ, or something heroic. If only she didn’t go about these insidious tasks so cheerfully. She ran right back to, and not away from, the scene of the crime. Her mashed freckled nose, eyes big and blue as globes, and that one blonde ponytail still hanging on for dear life makes me want to kiss her. I don’t. I make a sandwich instead. Out of the corner of my eye I see she has the dog’s mouth clamped shut with one hand and is beating him over the head with the other, using the headless Barbie he chewed up as her weapon of choice. He takes it as if he likes it. Having her has bent, but not broken, me. I don’t know how long this will last, or what might be next? Locusts…plague…boils? I manage to get her to eat a sandwich for lunch. As is her way, she falls asleep mid bite, at the table, never any wind down time. I carry her to bed knowing this reprieve will be short lived. I jump in the shower, and out, throw on clean clothes and run a brush through my hair. When I come out of the bathroom she’s up changing into her third outfit, pink sweat pants tucked into white vinyl boots with fringe, an orange and yellow ruffled dress, and her sparkly tiara. She’s got her second wind. Satisfied that all is momentarily well, I start throwing away whatever can’t be salvaged in the fridge. I’m on my knees cleaning. It’s too quiet. My skin feels electric. It hasn’t been quiet in three years. Relief washes over me like a gusher. She’s on the couch silent, perhaps content. I look closer. She’s sitting as close to the edge as she can without falling off, straight up from her spine, with her small, smooth hands folded in her lap. She’s a mess, her tiara crooked, halfway fallen off. Her head’s cocked sideways like she’s listening, waiting for a signal. She sees me looking at her and a grin stretches out her face. I see nothing amiss. I go back to my fridge. I check in on her again. She’s in exactly the same pose. I’m panicked. She looks like a doll, fake. She sees me. There’s that exquisite, terrible smile. Then I see it. The window by the couch is open. On the far wall, across from the couch, is the birdcage. Her brother’s beloved Gideon. He’s perched, taut. The birdcage door is open too. That’s what she’s been waiting for - the bird to figure out that he’s free. Everything moves at a glacier’s pace and at warp speed. I look back and forth, between the cage and the window. I can’t move. My son’s soulful, tear-filled eyes flash in my head. She points at the immobilized bird. I dive toward the cage. Gideon takes flight and with a few flaps of his lime green wings he soars toward the open window. He veers unexpectedly, crashes into the wall, and drops. She is euphoric, ecstatic, clapping, jumping up and down. “Fly, fly!” she cheers in that voice, not noticing or caring that he’s dead. Before I can think, I jerk her up and stomp to her room. I plop her, too rough, on her bed and leave to gather my wits. I know I have to walk away. It’s starting in earnest. I stand outside her room, gulping air. I can hear her singing. The words sound like rocks tumbled over metal. I look in and see her chubby fingers and hands making climbing motions. She’s singing Itsy Bitsy Spider. It’s a lost cause. All that’s left is the crying. I go in, sit on her bed and she climbs on my lap. My eye burns where her finger pokes it trying to give me an Eskimo kiss. We sit, quiet. I wonder if we can make it to the pet store and get a replacement bird before her brother gets home. I run a hand through her nest of hair. The little nubs are just starting to break the skin near her hairline. I can feel the spiked ends. Her short, pointed tail digs into my leg where she’s sitting on it. I don’t know how much longer I can hide it all. It’s been easy so far, since everything with her is a fashion statement; the horns help keep her crooked crown on. Her crazy pattern combinations serve as a distraction, a clever ruse. I keep watch on her teeth. Her incisors gleam sharp, jagged. I reach down to scratch my wrist. It itches, burns, feels uneven under my fingertips. I hold my arm out so I can see it better. I hear her breathing, heavy, a low and steady growl. She pats the hot, blistering skin. Boils.  Nothing rolled out the welcome wagon quite like the stench of a working ranch. Several thousand turkeys, and a couple hundred head of cattle, plus a few dogs, each with their own piquant perfume - manure, grainy feed, animal sweat and hair. “Hat up, girl.” Hank loomed over me, out of nowhere. His cap twisted sideways on his long head. The, I’m already hammered and it’s only noon, signal. “Huh?” Spending time with my mother’s new husband was the last thing I wanted to do. Drunk at home, drunk at someone else’s home. I’d had enough. “We saved the last ones for you gals.” “Last what?” I didn’t know where this led, but I knew I didn’t like it. “Bulls.” Hank slapped his dirty hands across his dirt covered Levi’s. “You’re gonna hold the bucket.” “What bucket?” “The nut bucket.” Hank tromped toward the chutes. **** Every year the neighbors, and the not so neighborly, swarmed the Cox’s turkey farm carrying country hams, potato salads, chocolate sheet cakes, and all the usual picnic grub. The Cox’s supplied the homegrown barbecue to thank the guys who helped cut the bulls. Out on this highway town nothing said “hoedown” like separating a bull from his balls. Donald Cox handed me a metal bucket. “Here ya go, little gal.” He looked as happy as I’d ever seen him. “Where’s your partner in-” “I’m here. What the-” Libby loped up, breathless. I was sure she’d been pried from her new boyfriend’s grasp. I’d been avoiding her since she’d snatched him, but now I felt relieved to see her. “Thank god,” I said. She smiled big at me, like she always used to, before boys arrived on our horizon. “Come on, sis,” Earl, Libby’s dad said. “Grab your side of the bucket, and get a move on.” Earl and Hank milled around by the cattle chute next to the bullpen. I didn’t do a headcount. A campfire roared, with a couple branding irons and knives in it. You didn’t have to know your way around a ranch to recognize either one. Jefferson Davis, the youngest of four Cox sons, (all the Cox boys bore presidential names, no one clued them in that the South never rose again) tended to the ironworks, shifting them around in the flames, their orange and gray tips glowing, silvery ashes floating upward like tiny angel wings. The smoky, hot smell of scorched steel and burnt wood wafted up. I felt nauseous. “You ever done this before?” I asked Libby. “Nope.” Libby flicked her long hair back, over her shoulders. “But, we gotta pretend we’re pros. Can’t embarrass ourselves in front of these assholes.” On this, we agreed. “Alright ya’ll, the bulls are gonna hustle through the chute…get branded and cut. Theodore Roosevelt does the cuttin’, and the droppin’. You stand…right here.” Donald grabbed us by the arms and planted us outside the ass-end of the chute. “When they hit the bucket - stay still. Don’t drop it. Can’t have dinner fallin’ in the dirt.” I’d forgotten - on purpose - that these inbreds ate the balls…mountain oysters. Right, that sounded better. “I don’t think Delilah's ever eaten a mountain oyster.” Hank jerked his cap off by the bill, wiped the moisture from his wrinkled forehead. “Have ya, sis?” He’d never called me “sis” before. Earl called Libby that all the time. Something warm under my breastbone spread across my chest and shoulders. I smiled, surprising both of us. “Nope. Don’t plan to start, either.” “Hank, you need to set that little gal straight,” Donald said. “She ain’t-” “Ya’ll knock it off. I never seen no girl eat mountain oysters.” Jefferson Davis had his hat off, and his courage up. “Never seen one holdin’ the bucket neither.” Donald humored his youngest son’s gallantry. “You’re right, son. Ain’t no gal worth a damn eats mountain oysters. But, a little bucket holdin’ never hurt anybody.” Jefferson Davis put his hat back on, and turned his attention back to the fire. I couldn’t believe it…of all the boys in the world to come to my aid. Stupid Jefferson Davis - the dork. “I think you’ve got a boyfriend, Delilah.” Libby giggled. No, you’ve got my boyfriend. “I’d rather eat fried balls.” I prayed Jefferson Davis would get in the way of the knife, and Mrs. Cox would finally have a daughter. “Load ‘em up, boys!” Donald and his little presidents took their places. “You gals hang on to that bucket and stand where I showed ya’ll…ass-end.” “OKAY.” Libby yelled, rolling her eyes at me. “Does he think we’re as brain dead as he is?” she jeered, in a whisper. “That a girl, sis.” Earl closed the chute door behind him and Hank. It looked surprisingly small. Theodore Roosevelt and Donald were already inside. Hank jumped up on the side, his head above everyone else’s. “Let’s get ‘er done.” Theodore Roosevelt said. Jefferson Davis hurried over with the still smoking, tools of the trade. “YO.” Theodore’s call carried over the top of the chute, the gate opened, and the first unsuspecting victim got shoved in to meet its fate. I felt numb all over. Libby and I stood like we’d been told, each of us gripping our side of the bucket handle, awaiting the grisly delivery. Don’t run. Don’t run. I couldn’t make up my mind if I did, or didn’t, want to look. Like watching a scary movie - I covered my eyes with the hand not holding the bucket, but peeked through the cracks of my fingers. When Jefferson Davis poked the foot-long knife through the chute I decided - but quick - and closed my eyes. Too bad I couldn’t cover my ears. The sounds would haunt me for weeks - the blistering sizzle of the hot iron when it seared flesh and hair, the sickening squish and slice through sinewy flesh right after Theodore’s command to, “Keep that tail out of the way,” and the pathetic throaty moans of the calves, who didn’t have any room to move, or choice in the matter. They were pressed into the confines of the chute, by Earl and Hank’s full body weight with their heads held fast by the horns. If that wasn’t enough to make a girl run screaming…there was the smell - putrid and sweet - of blood, and burning skin. I could taste my sour stomach in the back of my throat and nose. Donald opened the head end of the chute and the steer ran for its life. Mooing soprano. Well, I lived. I glanced over at Libby, with a weak sort of smile. My teeth, jaw, and neck ached from clenching. I felt drenched, my hand bruised from the bucket handle. My hair came loose from its ponytail and stuck, matted to my head. Libby looked as rough. We sighed heavy and started to laugh. At the same time, we looked down at the bucket then back at each other, crestfallen. It was still empty. We looked up to see Theodore Roosevelt climbing to the top of the chute with his gloved hand cupped, bloody. “Hoooeee...ladies, ya’ll got yourselves some mountain oysters.” He leaned down and dropped his testicular trophies into the bucket, with a wet and heavy plop. Libby let go of the bucket faster than you could crack a nut. Recoiling in horror myself, I was unprepared to bear the full weight with the one finger that still hung on to the thin metal handle. It tilted perilously, its innards dangling dangerously close to the dirt. Theodore Roosevelt yelled, “Shit,” and was just about to jump to the ground when I gathered my wits, and the balls entrusted to my care, yanking the bucket up toward my chin with both hands, righting its contents. Theodore’s exclamations roused everybody out of the chute. I gripped my gruesome prize. Hank raised his cap, and winked - proud of my grit. I didn’t know why I cared that he seemed proud, but I did. I stood still, basking, for as long as I thought proper, with a bucket of bloody gonads held against my chest like a gold medal. “Those’ll be fine eatin’, for sure.” Hank peered into the bucket, then turned back toward the chute. “Gotta man up, sis,” Earl growled. “Libby?” I nodded toward my pale friend. “Are you okay?” “Yeah…sorry. I’ll know what to expect now,” she whispered, shamefaced. “You want me to stand in for you?” Jefferson Davis turned cow eyes toward Libby. “No. I’m fine.” She patted his bony shoulder and he sauntered back to the flames. “Tell hop along Cassidy to mind his own business and clean his knife,” I said. “Come on, we better get back to it.” “Yep. Plenty more where those came from.” I tried to keep the smug look off my face. I held up under pressure, Libby didn't. She might have the guy, but I had Hank’s admiration, which somehow mattered, my dignity - and a pair of hairy, bloodied, lopped off bull balls. Theodore Roosevelt, back in the chute with the gate shut, yelled, “Yo.” I assumed the position. Bully, bully. |

Archives

August 2014

IF YOU LIKE THE SHORT STORIES YOU'LL LOVE HER TWISTED CRIME SERIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed