|

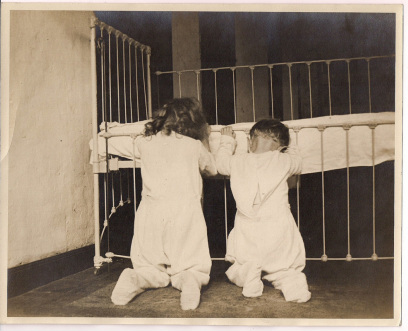

“God bless Mama-Daddy-Harry-Joanie-Tommy-Hazel-Jack-Bobby-Katie-Donnie-Rosie-and me, Emily,” I knelt on the wooden floor, in front of the not-big-enough double bed, with my sisters Hazel and Katie, in our too thin flannel nightgowns, passed down too many times. The cold climbed up our legs, through our kneecaps, like gladiola stems sucking up water in a vase. Mama held Rosie in her lap on the bed listening to our prayers. I kept one eye open. “Amen,” we chorused and climbed into bed. Me, Hazel and Katie slept together in the one bed. Rosie slept in Mama and Daddy’s room, still in her crib. We’d scootch over so she could move in with us next year, making it a foursome. Or, Hazel would leave. I knew she wanted to. The mattress creaked and groaned, protesting under our combined weight. Through no fault of our own, we rolled toward the sag in the middle. “It’s a school day tomorrow. No ruckus up here.” Mama turned out the light on her way downstairs with Rosie slung on her hip. We could hear “How Great Thou Art” in Mama’s off key soprano all the way down the steps, her ragged house slippers slapping her heels. We lay together in the dark, gripping each other’s clammy hands and waited. Almost every night Hazel murmured quietly, prayed, bargained, and cried herself softly to sleep. Sometimes he didn’t come. Most nights he was too drunk. We never knew if he would or wouldn’t. I stared at the ceiling, eyelids wide until they grew so heavy with sleep I couldn’t keep them open. I drifted off, Katie’s fingers intertwined through mine, a grip tight enough to make me lose feeling all the way to my shoulder. “Daddy, don’t. Please.” My eyes opened then whipped shut. My mouth filled with spit. Katie pressed her body against mine, hard. No air. We played dead so well, we almost were. Then we heard the slow, low metal sound of a zipper dragging down its ragged teeth. “No, no, no, no,” Hazel’s begging whisper. My skin felt prickly, burning hot. How long could I go without breathing? “Shhhh…now hush gal…give me your hand…” “Please. No.” “Shhh…shhh…” Katie pressed harder, the mattress squeaked. Our sweat-drenched gowns clung to our bodies, each other, and the threadbare sheet beneath us a dank pool. The coiled springs beneath us wheezed, keeping time with Daddy’s whimpering sounds. He sounded just like our dog Heidi when she had her puppies. Hazel cried. The wet smell stung my nostrils, mixed with the sour sickening stench that clung to Daddy. He rarely bathed or brushed his teeth. The raw meat and clotted blood he wore home from his butcher shop hung from his hair, stuck under his nails and smeared the front of his shirt where his apron didn’t cover - and the rotgut he swilled every night hung over him like a fog. Katie and I stayed straight and stiff, helpless against the onslaught of a father who reeked like a drunken, slaughtered animal. I gagged quietly in the dark. He left. Hazel rolled into a ball and sobbed without making a sound. We scooted toward her like we always did, but didn’t talk. Katie put her arms around Hazel’s back and I put my arms around Katie, a chain of girls, youngest to oldest. Like we did with Joanie. And like I will with Katie. She’s the next one up. Then it’ll be me. I’m not sure exactly what Daddy’s doing. I just know it’s bad and I know I can’t tell anyone, especially Mama. I know he takes his pants down. It makes me cry, and my stomach hurts all the time. I asked Joanie once, before she left home for good. She slapped me so hard my head hit the wall behind me, and my eyes bugged out. Then she knelt down, grabbed me tight, and pressed me to her chest. “I’m sorry, Emily, I’m sorry,” she said, her tears soaking my neck. “You don’t know anything. You’re just a kid.” I never brought it up again. No one did. I figure I’d find out soon enough. My guts churned. **** “Now you boys stay out of those woods,” Mama hollered after my brothers, Bob, Donnie and Jack, grabbing their lunch sacks, running out the kitchen door to school. The screen swung wide on its rusty hinges, and slammed. I never could figure why Mama fussed over the boys and those woods. They never took to ‘em. Not like me. Not far from our house, across from the Dietrich’s place, around from the burnt out Texaco gas station lay Doc Pritchett’s wooded land. Daddy called it 40 acres of waste ‘cause Doc would never clear, or sell it. Mama said he was too busy doctoring to bother with clearing or selling. But those woods made for a nice shortcut to and from. School was over a mile away. A quick dart through the corner section of Doc’s woods cut the walk in half. After the boys high-tailed it out I was the last one, stalling before school. “Dawdling,” Mama always said. “If I have to tell you to get going one more time…” Mama wiped baby Rosie’s Malt-O-Meal covered fat face off with the bottom of her apron and griped at me at the same time. “Girl, you’ll be late for your own funeral.” Why I would mind that, I couldn’t fathom, and said so. I snatched my brown bag off the chipped breakfast table quicker than she could swat me, elbowed out the screen door, and ran. Mama never said anything to me about the woods. She never did. **** I had good intentions, until I didn’t. I was running late. So, when I got to the place where I could’ve kept going the long way, I took the short way. I started through the woods to make up time. It got darker and cooler the deeper I went. At first, I walked fast. Then it was more like a lope. As my eyes adjusted to the dim light I gathered speed. Soon, I galloped along like a barn-soured horse at feed time. My feet hit the earth with sure strides. My leather soles crushed the dead leaves beneath them with a satisfying crunch, like smacking cornflakes in a paper bag with a rolling pin. I swapped my lunch sack from my left hand to my right and back again every few minutes. I felt sure I’d beat the clock. I galloped, grinning like the village idiot and about half way there when the toe of my two-toned shoe hit something soft, yet unyielding mid-stride. It stopped me cold, and dropped me like a sack of hammers. I landed on the dirt and twig covered ground with my, used-to-be-Katie’s, blue gingham dress up around my waist, with a thud and an oooof. The air slammed out of my lungs as my flat chest hit first, before my forehead, which made a sickening crack. I rolled onto my side and pulled my knees up. My head throbbed, sharp pain stabbed through it. I could hear myself moaning. I rocked from side to side on the sticks and leaves, trying to find air. After several minutes the cramps subsided. I could breathe again. I lay still. I wasn’t alone. My eyes, still shut tight, flew open. It didn’t occur to me to fake unconsciousness, which I’m good at. I sat up quick as Lazarus. Straight ahead of me was my lunch sack, sitting pretty as you please, where I’d flung it. I crawled back a few inches. There he laid, flat on his back, legs sprawled out, arms straight at his sides, neck bent at a funny angle. He looked broken - half covered in leaves, twigs, and dirt. From what I could see, he wore a dark suit and brown wing-tipped shoes like Pastor John’s. Or, like Mama would say, “a dandy.” I must’ve tripped over one of his legs. He didn’t look so good. I got close enough to poke him. His dark eyes peeked at me, barely open, the lashes matted and crusty. His mouth swollen, cracked, face green and sallow. He looked barely older than my brother Harry, who just turned twenty-one, and sickly, like he suffered from a bad case of the flu. His black hair slicked smooth, matted to his head. My eyes bulged like a bullfrog hit on the head with my brother’s flashlight, “You hurt, Mister?” I crept closer and saw the blood. His whole jacket soaked through with it, the ground beneath him covered in it. He smelled just like Daddy’s shop on slaughtering day, sickening, rank and sweet. I yanked my hand away and covered my mouth with it. Because I couldn’t help it, I studied his face. Even though I’d never seen a dead man before, I knew he was one. His eyes looked glazed, lifeless, like the lambs on hooks in the butcher shop. I started to cry. Usually, I don’t. Not unless there’s someone there to see me. I don’t know how long I sat next to a dead man, crying. He stank. I needed a plan. The only one I could come up with was to see if he had a wallet with something inside that might have his name on it. I used a stick to push his jacket lapel open. Nothing. I checked to see if the jacket had pockets, and found a folded up piece of paper and a stick of chewing gum. He probably carried his wallet in his pants pocket. How could I get him rolled over? If there was ever such a thing as dead weight – he was it. Luckily, I didn’t have to roll him far, more like a nudge. I scrunched up his wooly jacket, reached into his trouser pocket, and picked out his wallet - shaking the whole time. I didn’t look in it. I couldn’t waste more time. I snatched my lunch bag off the ground, threw in the folded up piece of paper, and the wallet. Thinking twice, I grabbed the gum and threw it in, too. No sense wasting a good piece of gum. It still had the wrapper on it. I ran for my life. One of us had to. It wasn’t going to be him. **** When I made it to class, I told Miss Parker I fell, which is why I got there late, and why I had a blue lump on my forehead. How I would let a grown-up know about the poor man, dead on Doc Pritchett’s land, I didn’t know just yet. If my mama knew I’d been in the woods I’d get the switch for sure. I’d have to think of a way to let someone know without tattling on myself. I’d have to worry about that later, after my head stopped hurting so much. He wasn’t going anywhere. **** “Emily, stop daydreaming, we’ve got customers,” my brother Harry said. It was my Saturday to help in the butcher shop. I ran scared. I’d gotten away with lying so far, but I still couldn’t think of a way to let anyone know about the dead man. Not without heapin’ a whole lotta trouble on myself. Luckily, with so many kids, Mama couldn’t keep us straight. I made her think she already knew I fell and hit my head against the table. All us kids tricked her like that. She just nodded and said, “It’s a long way from your heart” and went on about her business. What if I didn’t tell? The dead man would be no worse for the wear. I, on the other hand, wouldn’t be as lucky if my mama found out where I’d been. I kept my eyes on the ceiling, expecting a wallop from the heavens any second. The dead man’s wallet fit easily, tied around my waist, under my baggy dress. In a house with seven of ten kids still in it (there would've been eight, but Tommy had joined the Navy in ‘39), there’s no place safe to hide anything. But it kept coming loose, and I worried someone could see the bulge, even under my apron. “Harry, you get lunch. I’ll go after. Bring some back for your sister,” Daddy said. “Emily, get some more ground beef outta the walk in and hurry it up, you’ve been worthless all day. Head in the clouds.” I ran back to the big freezer and opened the heavy door with both hands. The icy blast of air hit my face like a slap. My jerking on the door loosened the wallet, and it slid down toward the ground. I crouched and caught it near my knees. I finally opened it. Earlier, I shoved the piece of gum, and folded up piece of paper in it, but couldn’t get away from prying eyes long enough to look at anything. His driver’s license read Wayne Hendrickson. He’d lived on West 58th Street, only 10 blocks from me. I unfolded the piece of paper, and read the type written note -“Everyone knows what you’ve been doing. You’re going to pay and rot in hell.” There were two, one-dollar bills in the fold. More money than I’d ever had in my life. At a penny apiece…I couldn’t even figure out how much candy I could buy. I knew it’d be a lot. I tucked the note back into the wallet and tied it onto my waist again, grabbing as many packages of ground beef as I could carry and went out front. Customer after customer came into the shop that day. Daddy’s butcher shop sat next to the town’s grocery. The grocery sold a lot of things. Like candy. All I could think about that afternoon was the two one-dollar bills. My mouth watered dreaming about the Tootsie pops and the Good News bars I’d soon eat. What could it hurt if I took just one dollar and bought some? The dead man couldn’t use the money. I looked up at the ceiling…so far, so good. I went to the restroom, loosened the string, grabbed a dollar bill out of the wallet, and waited for an opportunity. Harry’d gone home. Just Daddy and I stayed behind the counter. I should have thought of it earlier, before Harry left. Mrs. Wolanski took her pork chops off the glass counter, turned and walked away. I made my move. “Daddy, I’m going to get a soda at the grocery,” I said, cool as mama’s cucumber and purple onion salad. Hoping against hope he wouldn’t ask what I planned to pay for it with. Without looking at me, Daddy said, “We gotta clean up.” He shook his gray head. “Go on. Just go on and go home. You haven’t done me any good all day.” Victory. I’d forgotten Daddy had no interest in me. Yet. **** I heard my brothers say that Daddy came home drunk, barely standing, and late, that night. He stayed home two days in a row, walking around the house white as a ghost, and acting like one too. Never saying a word. Mama pestered him to go to the doctor. He sits on the edge of whatever chair he’s in and his eyes dart back and forth like a lizard looking for flies. Last night Donnie walked up behind him and said, “Daddy,” and he liked to put my brother through the wall. He stopped coming to our bedroom. I still felt scared. **** “Let the church say, Amen.” Every Sunday, Mama shuffled all of us off to church. Daddy never liked it, but he always went, and this Sunday was no different. He looked poorly too. It’d been over a week since he’d come to our room in the middle of the night. But I had other things to worry about. I’d been pondering my dilemma while we all loitered in the vestibule while Mama chatted with Mrs. Olsen and her spinster daughter, Olive. Trancelike, Daddy lurched into the church toward the pews. My brothers tumbled behind him. My sister Joanie stood with her husband Andy, and us. Joanie didn’t come to our house anymore. She got married quick, and now we only saw her here, on Sundays. Mama cried over it about once a month. I’d been thinking hard about how to have my candy and eat it too when I heard Joanie whisper, “…she’s messing with that furniture salesman, Hendrickson. Walt, or something or other.” I’ll tell you, I thought my tongue would fall out. Before I could drop dead, Olive whispered back, “And Nora’s a married woman…” “I know who-” I started to blurt out what I knew, but got a good cuff for my trouble. “Emily. Hush,” Joanie hissed. “You don’t know a thing about it. You’re just a kid." I kept my mouth shut after that. Most of the sermon passed in a blur, despite Pastor’s fire and brimstone threats. Bored, I gawked around, and who sat behind Daddy but Nora and her husband – Nora - who messed with Walt, or something or other, Hendrickson. Now, I didn’t know what “messing” entailed, but I caught a clue that it wasn’t good…apparently being married had something to do with it. From what I could recall, poor dead Wayne Hendrickson didn’t look old enough to mess with anyone. Nevertheless, he had enemies. According to the note, they knew what he’d done (and it must’ve been bad) meant for him to pay and burn in hell. I couldn’t figure out what, if anything, any of it had to do with Nora and her “messin." On cue, Pastor John, boomed, “Your sins will find you out!” and pointed right at Nora, directly behind Daddy. I jumped, and almost gasped. Before I could, Daddy sprang out of the pew, and bolted toward the door. **** The trail of blood led from Mama and Daddy’s bedroom to the bathroom, some on the white walls, drips, drops, splats, now congealed and almost black. “He’s sleeping now.” Doc Pritchard closed the bedroom door. “Close call, but he’ll be fine. He stitched up real nice.” Mama sobbed into her tissue, Rosie slung on one hip. Katie stood next to me, silent, lips pressed together so hard they’d all but disappeared. Hazel sat in Mama’s chair in the living room, staring out the window. “Why would he slit his wrists?” Mama almost wailed. “I don’t know if you don’t,” Doc Pritchard said. “He ran out of church like it was on fire. Something’s been weighing heavy on him,” Mama said. “I don’t know what.” Katie finally spoke, but she sounded funny. Like her back teeth were glued together. “When we got home, we saw the blood. I followed it to the bathroom…” She straightened her shoulders. “…there he was…on the floor.” “The razors still on the rug, by the bed.” Mama hiccoughed out the words. I tiptoed to my bedroom, worried that the look on my face would give me away. Somehow I felt at fault. God was punishing me for my deception. I needed to come clean. I could tell the Doc that a dead man lay rotting on his land. I could confess that I had his wallet, his money (well, most of it anyway) and his gum (no, I chewed that. It was stuck under our dresser for more chewing later). I could admit I’d lost his note. I could’ve…but…I didn’t. I wanted more candy. I still had a dollar and a half left. But, that posed another problem. The day I lost the note, the day I went to the grocery instead of helping Daddy clean up, Old Lady Taylor, the cashier said, “My, a whole dollar? How did a little girl like you get so much money?” I thought she’d call Mama, but just as my lip started trembling, Larry the bag boy with crooked eyes, dropped a bottle of Coke. It exploded on the concrete floor like a 4th of July firecracker. Old Lady Taylor hustled off to yell at him and I busted outta there like a rat with its tail in a trap. I ran my hand under the mattress, felt the wallet in its hiding place and decided to wait and see. **** The weeks passed. Daddy’s wrists healed and he went back to the butcher shop. No one mentioned “the incident,” at least not in my hearing, or out of my hearing when I snooped. Daddy still hadn’t come to our room and he still looked real sick. Mama got skinny from fretting, and I’d never seen Hazel happier. I’d waited so long to tell about dead Wayne Hendrickson and the lost note that I almost forgot it happened. My mouth stayed shut, my secret kept. His wallet lingered under our bed, the money still in it. I didn’t dare risk another candy buy. Time marched on. When the cops came to the store, it was my Saturday at the butcher shop. I saw the two of them, their dark blue uniforms sharp and crisp. They wore their hats at a jaunty angle on their heads and their badges shone, fastened to their chests. They had their heads down, talking low to my brother Harry, at the front of the shop. The jig was up - they’d finally come for me. What could I do but face the music? A life of crime wasn’t for me, not anymore. From behind the meat counter, I wiped my sweaty hands on my apron, then untied it and took it off. I could feel the tears gathering behind my eyelids. I took a step toward my fate when the gun went off. I didn’t know it was a gun then. I’d never heard a gunshot before. I heard a deafening, ear-ringing crack, felt the back of my neck and arms get wet. My shoulders vibrated. I saw my brother Harry’s face crumple; the cops jumped and ran toward me. The bright red splatters on the glass counter in front of me made me turn around, wondering where they’d come from. The wall behind me looked like Rosie’s highchair tray when she ate spaghetti - red everywhere, and something else. Something gray and gummy ran down the white tiled wall, some stuck there like the chewing gum under my dresser. Daddy lay crumpled on the ground, one eye open. The other eye was gone, along with most of his head. I think I saw it, or part of it, rolled up against the baseboard. The same gray slime running down the wall with the blood dribbled out of the stump that was Daddy’s skull. I don’t remember the rest of that day. **** It’s just us kids and Mama now. Harry runs the butcher shop. Me, Katie, Hazel and the rest of the boys help out. Rosie doesn’t care what anyone does. Joanie and Andy come over for dinner after church every Sunday. Tommy's coming home on leave next week. Hazel sings us to sleep at night. I didn’t know what happened for the longest time, other than Daddy shot his own head off. I didn't even know he had a gun. I’m pretty nosy though, a “busybody” Mama says, and that’s how I heard. Somebody found poor, dead Walt Hendrickson. I don’t know who or how. The cops came to the store that day to ask where Nora lived. Folks not familiar often stopped at the grocery or the butcher shop to ask directions, especially since the gas station burned down. Nora’s husband had killed poor Wayne. I never did know Nora’s husband’s name. I guess Wayne’s “messing” with Nora really was bad - bad enough to make her husband kill him and leave his body in the woods. I held my breath wondering if they’d say anything about Wayne’s missing wallet. I still had it under my bed, but I finally threw that old chewing gum away. It didn’t taste like anything anymore, so I had to. I don’t know why Daddy blew his brains out. I heard they found a note in his pocket. Maybe that explained it, but I don’t know. I’m just a kid.

15 Comments

|

Archives

August 2014

IF YOU LIKE THE SHORT STORIES YOU'LL LOVE HER TWISTED CRIME SERIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed